The future of mental health care: Why the “well” majority matters

In my previous article in this “thinking beyond therapy” series, I suggested that we need a perspective shift in mental health. A shift from thinking about mental health only in terms of symptoms of a disorder, to the full continuum from mental health disorders to flourishing, and from thinking about mental health care only in terms of symptom reduction. In the spirit of this perspective shift, I want to flip the typical narrative.

Rather than talking about the 40% of U.S. adults who are reporting symptoms of depression, let’s focus instead on the 60% of U.S. adults who aren’t currently reporting these symptoms. How many of those are at risk of becoming depressed in the future unless they engage in preventative measures? Ignoring this part of the population simply because they are comparatively well would be like telling someone who is in the normal weight range that they don’t need to worry about exercising or about what they eat.

Managing your mental health also takes work.

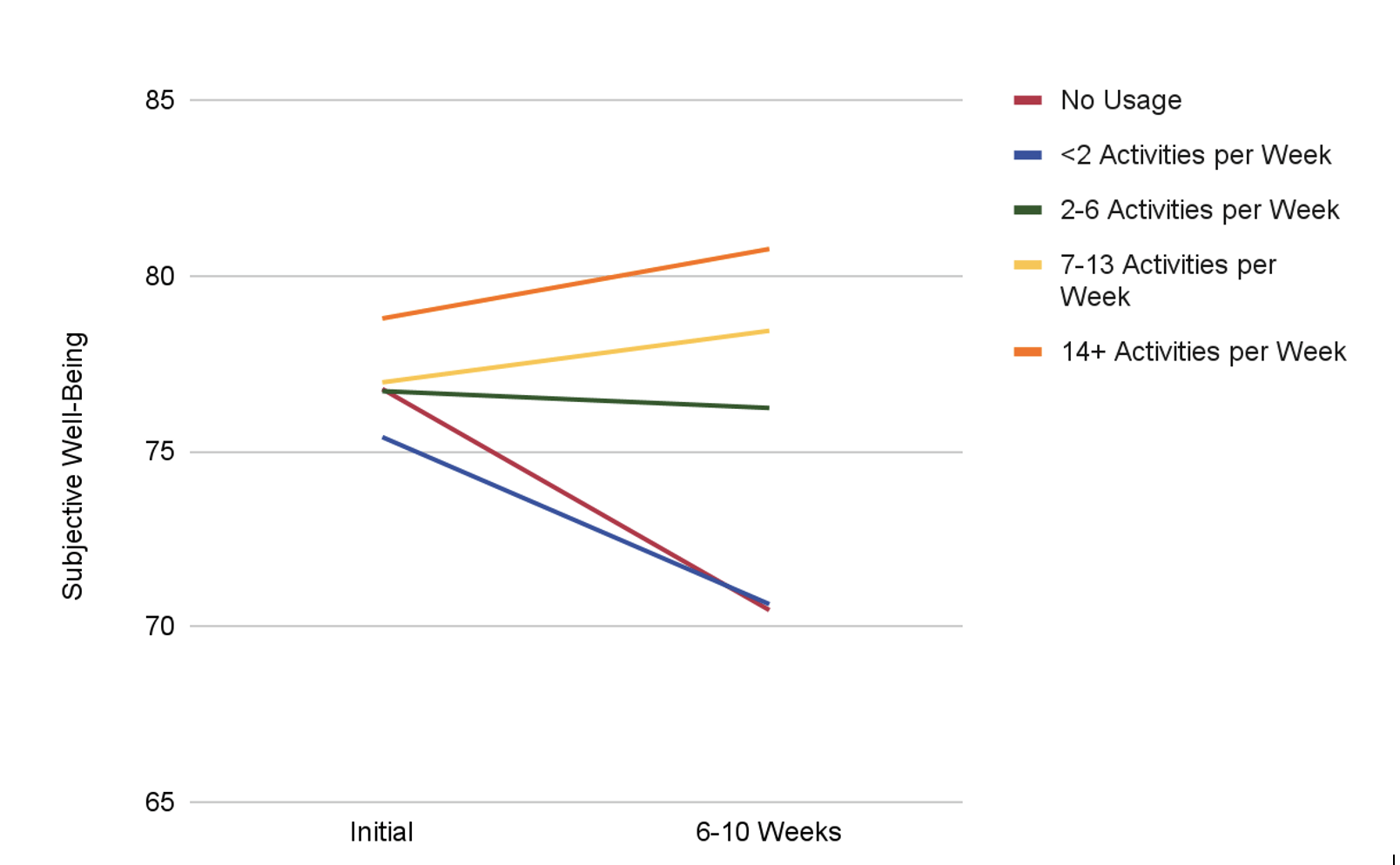

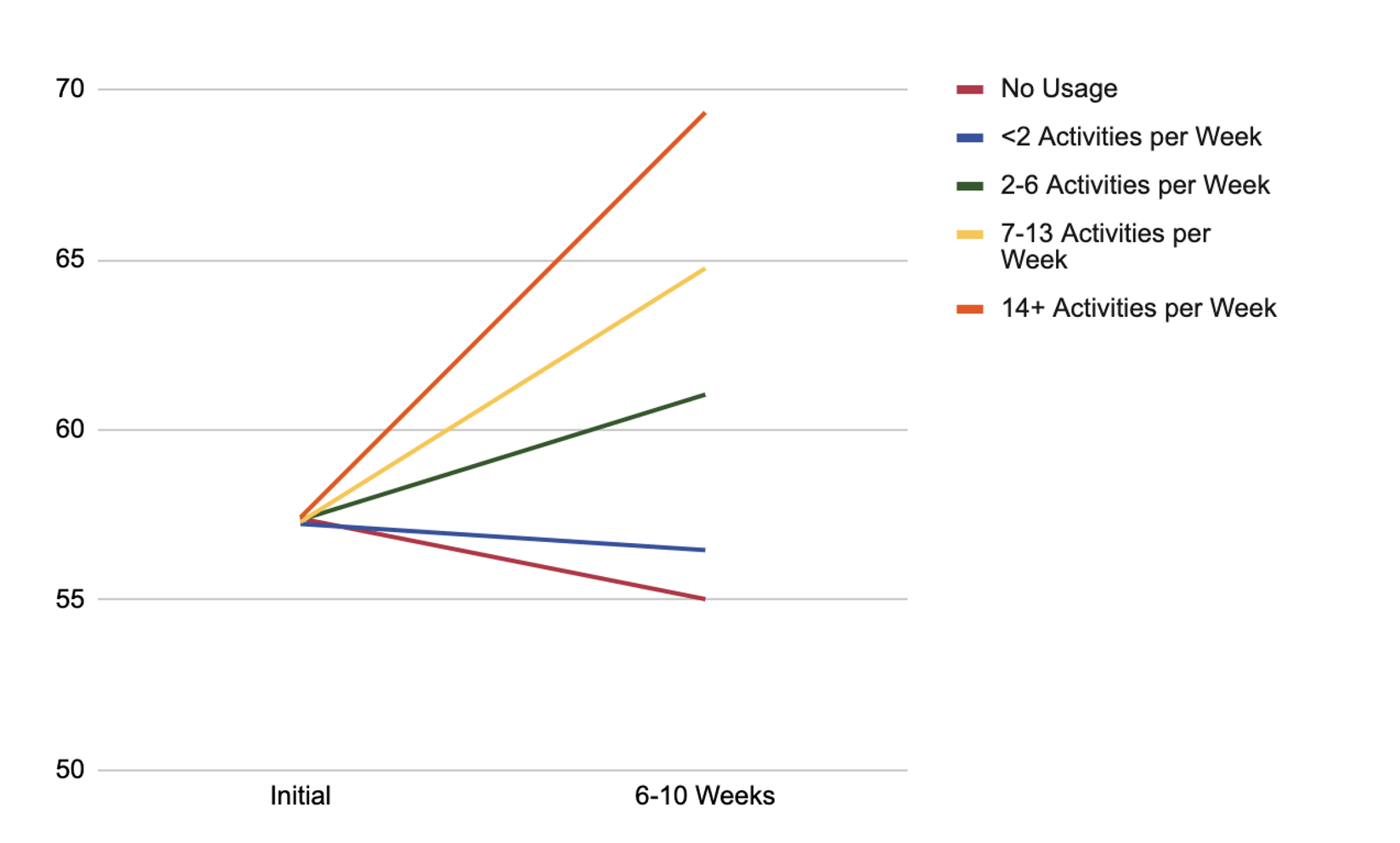

In fact, in our research, we’ve found that the people who already have relatively high levels of well-being tend to report lower levels of well-being after 6 to 10 weeks if they aren’t regularly engaging with our platform. More specifically, users who are estimated to have no symptoms, or mild symptoms, of depression1 when they initially signed up for our self-guided wellness program, have well-being scores that worsen by 4-8% during the first 6-10 weeks. When they complete at least one activity, but less than 2 activities per week (what we consider suboptimal usage), their levels of well-being worsen by 1-6%.

It’s only the users who are completing at least two activities per week who are at least maintaining their well-being levels. And if they increase their engagement to at least 7 activities per week, we even see improvements in well-being ranging from 2% (among those with no estimated symptoms of depression) to 13% (among those with mild estimated symptoms of depression).

In other words, even if you’re feeling “well” psychologically – it’s probably good practice to engage in exercise that helps to strengthen, or at least maintain, skills like empathy, emotion regulation, resilience, and cognitive and social skills, on a regular basis.

Figure 1. Changes in Subjective Well-Being Over 6-10 Weeks Among Twill Users Estimated to Have No Initial Depressive Symptoms Based on Engagement with a Self-Guided Digital Mental Health Intervention.

Figure 2. Changes in Subjective Well-Being Over 6-10 Weeks Among Twill Users Estimated to Have Mild Initial Depressive Symptoms Based on Engagement with a Self-Guided Digital Mental Health Intervention.

Why We Should Care About this “Well” Majority

Just like physical health, without routine mental health care, people who have high levels of well-being may not remain “well” over time. And given that the average time from symptom onset to a diagnosis of depression is about 8 years, with excess costs associated with depression increasing over time, closer to the time of diagnosis, prevention is significantly cheaper than treatment. We don’t ignore heart health until we find ourselves in the emergency room because of a heart attack – and we shouldn’t wait until there’s a significant problem with our mental health either.

But without better guidance about what routine mental health care looks like, people may be relying on services they don’t really need for mental health support. Perhaps in an ideal world, we’d all have a therapist we see for an annual mental health check-up, like we see our PCP for our annual well visits. But given the shortage of therapists, this just isn’t feasible. As it is, therapists are reporting significant increases in patient referrals post-pandemic, which has led to significant increases in wait times. Without making a change, we’re projected to be short up to 17,705 psychiatrists by 2050.

So driving more people to therapy shouldn’t be the only answer – in fact, that could make things worse for the people who really need it. For example, national trends show that utilization of mental health care services among children and adolescents has increased. While the proportional increase of these services is greater among those with severe impairment (those who really need the services), the absolute increase is larger among those who have little to no impairment (the ones who probably don’t). Almost double the number of youths with little impairment are using mental health services relative to those with severe impairment.

Practically speaking, this means that because services are being utilized by people who may not need that level of care, those who need it may not be able to access it. We need to drive the right people to therapy and provide alternative solutions for those with little to no impairment.

Evidence-based, self-guided digital mental health interventions seem to be the most feasible solution to providing routine mental health care to the 150+ million U.S. adults who may not need therapy. Increasing adoption of these interventions among the “well” majority may help to ease the burden on mental health care practitioners, thereby allowing the other 40% of the population to access mental health services more easily, and more quickly (and some would argue that the people who actually need therapy is just a small portion of the people experiencing symptoms). What’s more, while people may not be in the best position to determine what level of care they need – particularly given that as many as 17% of U.S. adults may not even recognize that they are experiencing symptoms of depression – digital tools can be used to triage users to the right level of care, initially and over time by tracking changes in their mental health.

These tools already exist – and while not all of the digital mental health interventions on the market are evidence-based or scientifically validated, many are. But there continues to be a prevailing narrative that the interventions are not particularly effective – a narrative that is based on research that evaluates digital mental health interventions based on the reduction of symptoms of depression and anxiety.

We need to start measuring success in other ways, particularly if we care about the benefits of such interventions for the individuals who are not experiencing symptoms (and I hope that I’ve convinced you that we should). The benefits of mental health care aren’t limited to those who are feeling unwell – we just need to adjust our views that mental health care is just about reducing symptoms, and that therapy is the only answer.

——-

1 Dario Health estimates the severity of Twill Therapeutics users’ depressive symptoms using our proprietary measure of subjective well-being, which has been shown to be highly correlated with validated measures of depression, like the PHQ-9. Using an established statistical regression, scores on our proprietary measure are used to estimate PHQ-9 scores, to give an estimate of depression symptom severity category.

Dario has extensive experience in cardiometabolic, musculoskeletal, and behavioral health, with proven results that demonstrate meaningful outcomes.

Learn more by requesting a demo today.

Request a Demo